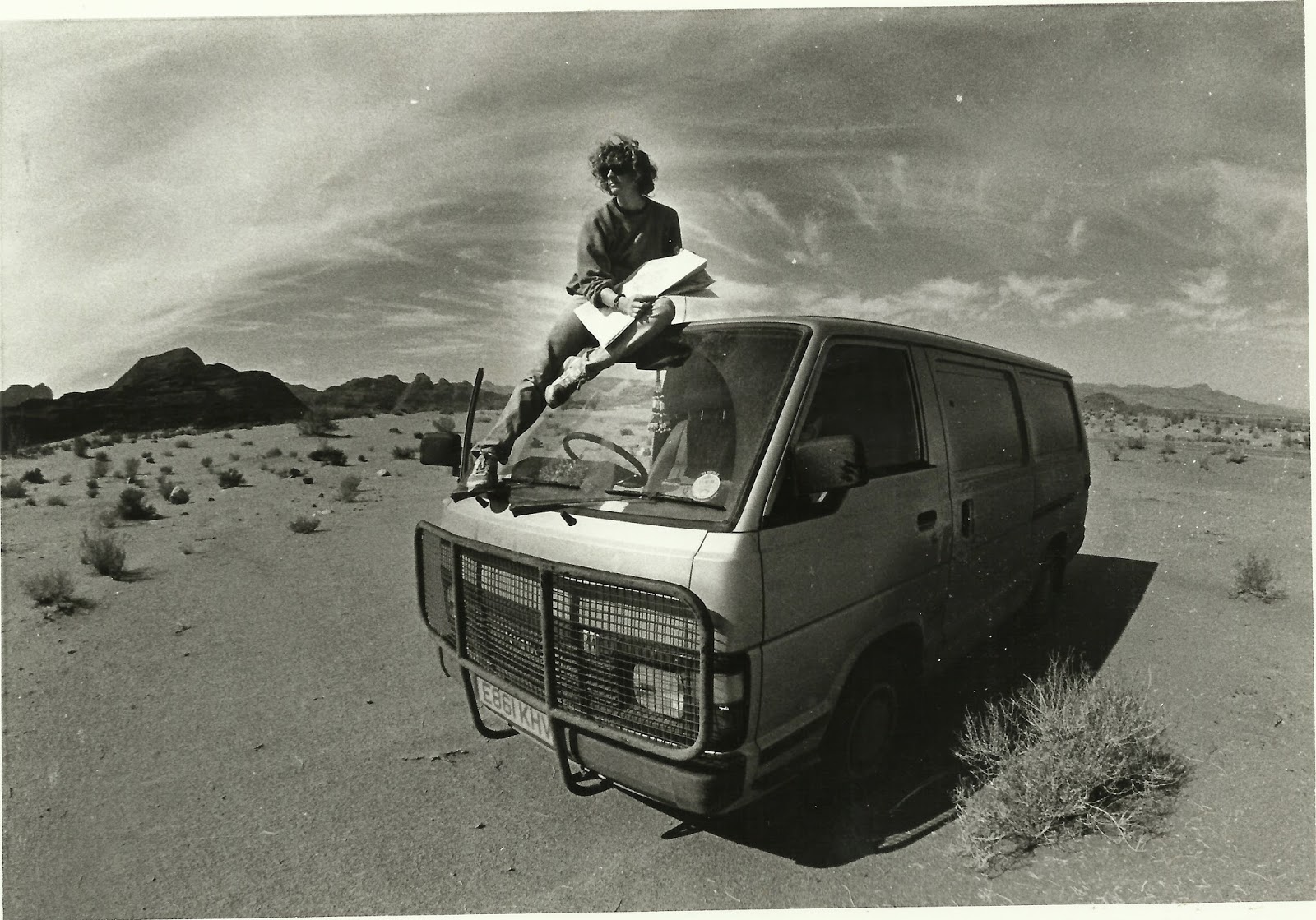

In a former life I knew this person . . . S.L.

R.P. in Wadi Rum, Jordan

A Winter in Crete - by Rachael Pettus

I spent the autumn and winter of '91 in Crete, arriving as the trees changed colour and the olive harvest began; as the snow line started creeping down the flanks of the three great mountain ranges that form the spine of an island that I have come to love over the last two decades. I was living in my van, a converted 1987 right-hand-drive Toyota Hi-Ace with British plates that I had driven from Ireland to Egypt and back the long way around via Israel, Iraq, and Turkey. And fleeing the Northern winter again, I sought refuge in Greece and took the ferry to Heraklion.

I was alone. And I was tired.

I read Cretan history to better get to know the island that I planned to call home for the next few months, and became caught up in the events of the Second World War. German paratroopers had landed at Maleme and finally captured the island, forcing the Commonwealth defenders to trek over the ranges to the havens of the southern harbours and eventual evacuation to Egypt. Cretan resistance, supported by British irregulars, had flourished throughout the war, and when I finished Antony Beevor's book on the Battle of Crete, I started on others including Giorgos Psychoundakis' account of his role as Patrick Leigh Fermor's messenger in The Cretan Runner.

S.L.: The German invasion of the island from the air - a revolutionary tactic at that time - turned into the closest-run battle of the war. On day 2, 21 May, the Allied forces withdrew from Hill 107, leaving the airfield at Maleme effectively undefended. This allowed German forces to finally use the airfield to fly in reinforcements. The slaughter of German fallschirmjäger on the first day by New Zealand, Australian and British troops was so great that if just one Allied platoon had still been in place by Maleme airfield the next morning, General Student would have been forced to admit defeat. Instead, the psychological shock effect of paratroopers was so great that a smaller airborne assault force was able to defeat a larger garrison.

During the battle for Crete, the island was defended by only limited Greek and Allied forces, as the Cretan 5th Division had been transferred to mainland Greece the previous November. However, the determined resistance of the islands civilian population was such that the battle of Crete lasted several days and cost the lives of 4,000 German paratroopers. Crete fell definitively on 29 May, having endured longer than the time needed to occupy the whole of France - S.L.

Rare color photo of German Fallschirmjäger in Crete on captured British vehicle. Note the Arabic writing on the vehicle's plates.

Her Story Continues . . .

I travelled all over the island, spending time on the rugged south shore and in the east, but as winter drew on I moved closer to the north-west port town of Chania, and since the war was an interest, gravitated to the German military cemetery on a hillside above Maleme. There was no museum or visitor centre then, just an asphalt parking lot and a small shack for the caretakers. I used to park up in a corner of the lot most evenings, appreciating the security that a cemetery, particularly a military cemetery, can give to a woman alone. Few people like being caught among graves in the dark, and the graves of soldiers – even enemy soldiers – have a hallowed quality.

The elderly groundsmen never bothered me. They would smile and nod each morning as I made tea or sat outside to read or write when the weather was warm. I spoke no Greek then, and hesitated to address them in German, but we had a benign relationship and I'm sure that they would have given me a hand if I ever needed help. Except for occasional expeditions to Heraklion to visit a friend or to Asi Gonia to visit Psychoundakis' home village (where I joined in the olive harvest and watched one of the last of the old stone presses turn huge quantities of fruit into gallons of spicy fruity oil), I spent much of the winter there.

Life rolled on. I married, had children, and settled in Cyprus, but I never lost my feeling for Crete or my interest in the island's recent history. In February 2006, flicking through the English press, I came upon Psychoundakis' obituary and read it through, remembering that long ago winter. Toward then end of the piece, I read with increasing disbelief: Psychoundakis, the writer and Resistance hero, had spent his last few decades as a groundsman, tending the graves of his former enemies at the German War Cemetary at Maleme with Manolis Paterakis, a fellow fighter.

One of the old men who had smiled and nodded to me each morning as I had read my way through the exploits of Patrick Leigh Fermor and his rag-tag band of warriors had been none other than The Cretan Runner himself.

"Middle of Nowhere, Directly Above the Center of the Earth"

There's something about this memoir that evokes a sense of a soul, cast adrift . . . having done my own share of wandering, it struck a chord . . .

STORMBRINGER SENDS

No comments:

Post a Comment